Firstly, such deep and buoyant gratitude to those who have supported me financially, emotionally, and energetically in my return to university life. After 3 decades in the creative and healing arts, shifting to science has been huge, so your faith in me has really carried me along. Also, with so much change in the systems themselves over the past 30 years, a good deal of my learning curve has been just figuring out where to find things, how to submit things, and how it’s all measured.

The context is just as crucial as the content.

Relatively early in the term, a fellow student said something about being happy as long as she passed, and that changed everything for me. It’s been so long since I’ve paid attention to grades and, without thinking, I slid right back into what I knew way-back-when. Unlike the breakneck speed and near-avarice with which I threw myself into undergrad, now I’m approaching it more like a dance between really learning the material and doing what’s needed to pass the courses.

You’d think they were the same thing, but it’s a matter of intention. I intend to investigate what I’m drawn to amongst the requirements in conservation, sustainability, climate change, problem solving, research methodologies, scientific writing, and the geospatial technologies that so effectively map and communicate data. Along the way (and already I feel it percolating inside me), I’ll nose my way into a focus area for my masters thesis.

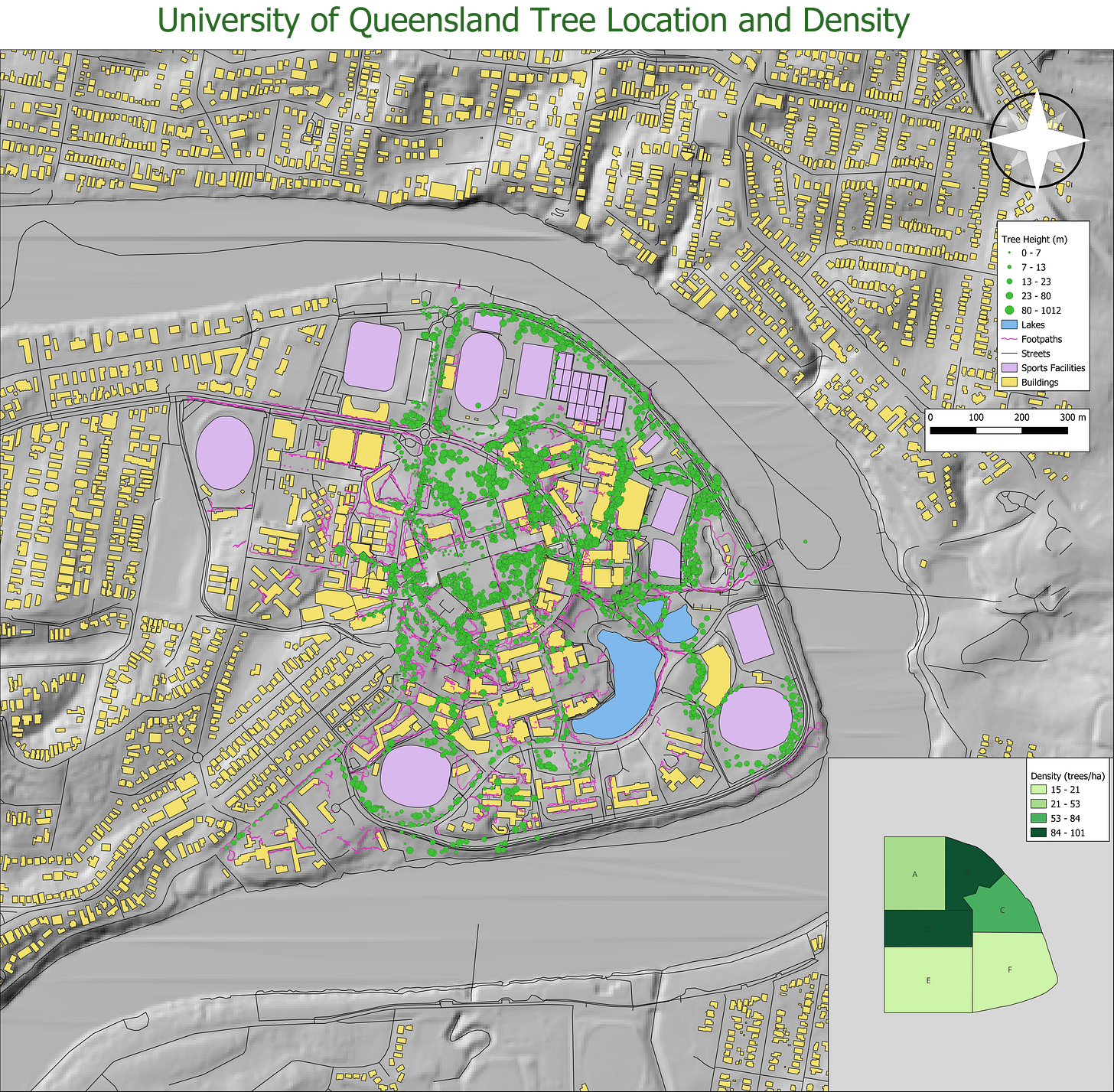

Here’s a map I made of the campus that conveys a class-wide, in-person survey we did of trees on campus and their approximate height.

And here’s a poster I made to communicate research done around community participation in the lead-up to the 2032 Olympics.

I was surprised to find how much I love mapping, but then I remembered that one of my playthings as an only child was a spinning globe of Earth. I made up a game for myself that I shared with friends who came to play. One person spins the globe while the other person spins in space until the spinner stops the globe and looks to see where her finger is. Then together we’d make up a story of our life on that part of the planet. For you astro-geeks, there’s an early sign of my Sagittarius Ascendant, Makemake in the 9th, and Chariklo (the Spinner) conjunct Mercury in the 4th!

So here’s my first StoryMap! This means of communicating is a great way for me to utilize some of the many strands of art, healing, and cultural inquiry I’ve had the great good fortune to weave into the loom of my living over so many lands and waters. The topic of that storymap is my relationship with water that really sparkled up into my awareness from 2014. Next on my list is to make a storymap of my resume/CV.

I am so grateful that a dear friend has made it possible for my wee Mama Bear to make the epic journey from upstate New York to Brisbane for the summer holidays. It’s super hot already and we’re fortunate to be house/cat-sitting a place with a small pool to help stave off the weight of the heat.

Again, thank goodness I’m flexible and didn’t break my knee in my recent bike accident on the way to teach kids yoga. It’s still sore. But the good news flash is that I’m nearly at 1700 kilometres since early August! That’s about 400km’s per month or 100 per week. Even though I’m slightly more cautious now, I still love moving through the world this way, especially when the frangipani and other flowering plants and trees are wafting on the winds.

Below, should you care to read on, is an essay on fire resilience that I turned in for the Conservation and Wildlife Biology course. As you can see by the extensive references at the end (that are nearly as long as the writing!), so much of what I’m learning is how to write succinctly and how to reference the research properly.

That’s enough updates for the moment! Next up is the Rounds 3’s of Brightest Spring for the Southern Hemisphere folk and First Winter for the Northerners.

Much love,

Mox

GYACK CALLS US TO CORROBOREE ON ITS CONSERVATION

Why Pseudophryne pengilleyi Deserves Continued Protection

Frogs, by their nature, are inseparable from their environment, as they absorb water through their skin, and are therefore acutely sensitive to any contaminants in the water. Although all creatures are inextricably linked to all other creatures and plants, with frogs this web of inter-relations is more direct and obvious, which is why they are considered an ‘indicator species’. Frogs are the proverbial ‘canary in the coalmine’.

Just as the nature of a First Peoples’ Corroboree, or sacred ceremony, is exclusive and private, so too are the lives of the paper-clip-sized Gyack/Northern Corroboree frogs that make their breeding nests in the moist shelter of the sphagnum bogs and then migrate to the nearby woodland fens of the Australian Alps. Their specialised habitat, the ecological community of Alpine Sphagnum Bog and associated Fens was declared Endangered in January 2009 (Department of the Environment, 2015).

“The northern corroboree frog faces considerable inherent risk due to its specialised life history. It has a very low clutch size, each female breeds only once each year, and the tadpoles are slow-growing, spending three months or more in the shallow pools. Whilst this life history has evolved in response to a relatively stable, cold, low nutrient environment, it also reduces the ability of the species to recover quickly during favourable seasons and places it at risk from any long-term disturbance or change that affects the breeding sites.” (ACT Government, 2011). As a habitat specialist in an isolated and endangered ecosystem, and with a life cycle that requires about 3 years to reach reproductive age, destruction of their essential moisture levels caused by severe fires increases the Northern Corroboree’s precarious status (Ensbey et al, 2023). In addition, this isolated environment that is unaccustomed to fires means there are “limited opportunities for postfire recolonization without human assistance” (Beranek et al, 2023).

The Northern Corroboree frog (Pseudophryne pengilleyi) has been battling threat after threat since the mid-1980’s when Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, an amphibian chytrid fungus responsible for the virulent chytridiomycosis disease, decimated the endemic population and propelled them into threatened species status internationally, nationally, and at the ACT and NSW state levels (ACT Government, 2011). An active recovery program has been in place since 1996 and insurance populations were started in 1997 through captive breeding programs that have carried on to present time (Soorae, 2018).

After periods of drought that severely impacted their breeding, as well as exposure to the devastating fires in 2003 that swept across Kosciuszko National Park, they were declared endangered, and by 2013 these iconic frogs had been elevated to Critically Endangered (DCEEW, 2013).

The Federal Priority metrics for calculating support for a species all point to continued conservation and protection measures for Pseudophryne pengilleyi. With an IUCN pre-fire conservation status score of 4, or Critical, as well as a pre-fire Imperilment score of 4, a Declining population trend, and their natural habitat classified as Highly-Range Restricted, it is no wonder that the 2019/2020 fires that overlapped 60% of their habitat gave them a Fire Overlap score of 3 and an overarching Risk Due to Imperilment and Fire Overlap score of 7 (DCEEW, 2020).

The 2019/2020 fires burned through the in-situ carefully-constructed refuge area only a month after reintroduction of 115 frogs that had been bred in captivity. Once the fires abated, researchers found 40 of the 115 still alive, having survived the fires by huddling together 10-30cm below ground, exhibiting a species-saving fire-resistance behaviour. (Tydd, 2020)

Not only is protection and support essential for perpetuating the Northern Corroboree, efforts to secure the future of this culturally significant creature in Australia serve to support amphibian conservation globally. Recent years have seen innovations in assisted reproduction (Silla et al, 2018), bioacoustic-based citizen science tracking (Rowley et al, 2019), immunity enhancement against the chytrid fungus (Edwards et al, 2017), and ex-situ conservation programs to cultivate insurance populations for reintroduction into the wild (McFadden et al, 2018).

Additionally, in-situ refuges that protect the frogs from threats, such as the deadly chytridiomycosis disease and ongoing habitat disturbance and desecration by weeds and feral horses, pigs and deer (Foster & Scheele, 2019), have benefitted both Pseudophryne pengilleyi directly, as well as furthering the urgent innovations needed in amphibian conservation more generally. Research applications such as these support worldwide efforts to redress the estimated 50% of amphibian species (about 4,000 of the total 7,900) that are at risk of global extinction (González-del-Pliego, 2019).

A key cultural opportunity exists in continuing to protect and reinvigorate the population size of Gyack/Northern Corroboree/Pseudophryne pengilleyi. The frogs themselves benefit of course, as does their equally endangered habitat, and there is also benefit for the wider web of relations that their threat of extinction represents. As the health of frogs cannot be separated from the health of the watery regions they call home, so First Nations cannot be separated from the Country they call home. “Just as environmental water is important for improving river health (Poff et al. 1997; Growns 2016; Williams 2017a), the recognition of cultural water is an important restorative healing mechanism for Aboriginal Australians.” (Williams et al, 2019)

“The project is designed to reconnect the Wolgalu/Wiradjuri community of Brungle Tumut to a species of ecological and cultural importance. Significantly, the northern corroboree frog was connected to Wolgalu/Wiradjuri annual ceremonies in the NSW High Country (Alpine region) (Williams, Connolly, and Williams 2019, 268). Thus, ours is a cultural revitalisation project. In the words of trawlwulwuy countrywoman Emma Lee (quoted in Tynan 2021, 601), to protect the corroboree frog the project aims to reclaim Wolgalu/Wiradjuri’s web of relationships that are mediated through country.” (Slater, 2021). The benefits of one are shared by all.

References

ACT Government. (2011). Northern Corroboree Frog (Pseudophryne pengilleyi). Action Plan No. 6. Second edition. ACT Government, Canberra. https://www.environment.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/576550/Northern_Corroboree_Frog_Action_Plan_-_Combined.pdf

Beranek, C. T., Hamer, A. J., Mahony, S. V., Stauber, A., Ryan, S. A., Gould, J., Wallace, S., Stock, S., Kelly, O., Parkin, T., Weigner, R., Daly, G., Callen, A., Rowley, J. J. L., Klop-Toker, K., & Mahony, M. (2023). Severe wildfires promoted by climate change negatively impact forest amphibian metacommunities. Diversity & Distributions, 29(6), 785–800. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.13700

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. (2013). Advice to the Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities from the Threatened Species Scientific Committee (the Committee) on Amendment to the list of Threatened Species under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act). https://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/species/pubs/66670-listing-advice.pdf

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. (2020). Revised provisional list of animals requiring urgent management intervention. https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/biodiversity/bushfire-recovery/bushfire-impacts/priority-animals

Department of the Environment. (2015). National recovery plan for the Alpine Sphagnum Bogs and Associated Fens ecological community. Department of the Environment, Canberra. https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/alpine-sphagnum-bogs-associated-fens-recovery-plan.pdf

Edwards, C. L., Byrne, P. G., Harlow, P., & Silla, A. J. (2017). Dietary Carotenoid Supplementation Enhances the Cutaneous Bacterial Communities of the Critically Endangered Southern Corroboree Frog (Pseudophryne corroboree). Microbial Ecology, 73(2), 435–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-016-0853-2

Ensbey, M., Legge, S., Jolly, C. J., Garnett, S. T., Gallagher, R. V., Lintermans, M., Nimmo, D. G., Rumpff, L., Scheele, B. C., Whiterod, N. S., Woinarski, J. C. Z., Ahyong, S. T., Blackmore, C. J., Bower, D. S., Burbidge, A. H., Burns, P. A., Butler, G., Catullo, R., Chapple, D. G., … Fisher, D. O. (2023). Animal population decline and recovery after severe fire: Relating ecological and life history traits with expert estimates of population impacts from the Australian 2019-20 megafires. Biological Conservation, 283, 110021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2023.110021

Foster, C. N. & Scheele, B. C. (2019). Feral-horse impacts on corroboree frog habitat in the Australian Alps. Wildlife Research (East Melbourne), 46(2), 184–190. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR18093

González-del-Pliego, P., Freckleton, R. P., Edwards, D. P., Koo, M. S., Scheffers, B. R., Pyron, R. A., & Jetz, W. (2019). Phylogenetic and Trait-Based Prediction of Extinction Risk for Data-Deficient Amphibians. Current Biology, 29(9), 1557–1563.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.04.005

McFadden, M.S., Gilbert, D., Bradfield, K., Evans, M., Marantelli, G., & Byrne, P. (2018). The role of ex-situ amphibian conservation in Australia. In H. Heatwole & J.J.L. Rowley (Eds.), Status of Conservation and Decline of Amphibians: Australia, New Zealand, and Pacific Islands, (pp 125-140). CSIRO Publisher. DOI: 10.1071/9781486308392

Rowley, J. J. L., Callaghan, C. T., Cutajar, T., Portway, C., Potter, K., Mahony, S., Trembath, D. F., Flemons, P., & Woods, A. (2019). FrogID: Citizen scientists provide validated biodiversity data on frogs of Australia. Herpetological Conservation and Biology, 14(1), 155–170.

Silla Aimee J., McFadden Michael, Byrne Phillip G. (2018) Hormone-induced spawning of the critically endangered northern corroboree frog Pseudophryne pengilleyi. Reproduction, Fertility and Development 30, 1352-1358. https://doi.org/10.1071/RD18011

Slater, L. (2021). Learning to Stand with Gyack: A Practice of Thinking with Non-Innocent Care. Australian Feminist Studies, 36(108), 200–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2021.1998883

Soorae, P. S. (ed.) (2016). Global Re-introduction Perspectives: 2016. Case-studies from around the globe. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Re-introduction Specialist Group and Abu Dhabi, UAE: Environment Agency- Abu Dhabi. xiv + 276 pp.

Tydd, M. (2020, December 21). The race to save the corroboree frog - How bushfires impacted UOW’s recovery program. University of Woollongong Australia. https://www.uow.edu.au/the-stand/2020/the-race-to-save-the-corroboree-frog.php

Williams, S., Connolly, D., & Williams, A. (2019). The recognition of cultural water requirements in the montane rivers of the Snowy Mountains, Australia. Australasian Journal of Environmental Management, 26(3), 255–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/14486563.2019.1652211

Wow! Just Wow! Very interesting! So proud of you! Your writing is scientific and elegant!!!